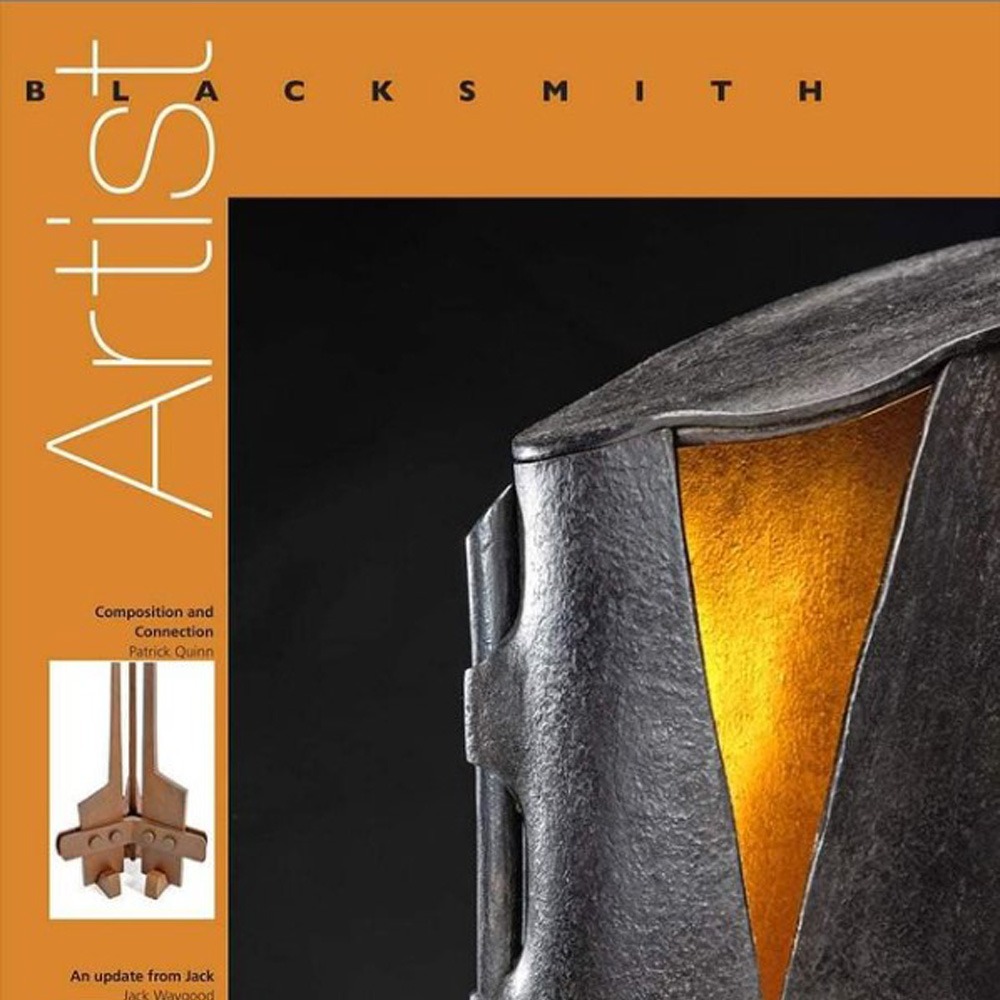

Calnan & Anhoj, Sculptors. Artist Blacksmith Magazine 2021

Calnan and Anhøj: Sculptors

Gunvor Anhøj and Michael Calnan find inspiration in the landscape of County Wicklow, Ireland. They both emphasise the importance of not overthinking ideas. Article in Bristish Artist Blacksmith Associations Magazine, March 2021.

Gunvor Anhøj

I met Michael whilst in college at Hereford; we have been working together since and are now set up in County Wicklow, Ireland as Calnan & Anhøj. It’s very useful being two in a studio, that way you can get the honest opinion from someone you trust, at that point where you might otherwise be stuck. Our styles are quite different, but we do swap ideas. I am often inspired by the woodlands surrounding us here at Russborough House, in County Wicklow where our forge is based. Over the years, I have developed a creative routine. I gain visual inspiration on walks, often resulting in ideas on which I don’t allow myself to ponder for too long, in order to retain the original flash of inspiration. The trees revealed themselves to me as inspirational for the first time during a winter where the dramatic trunks were exposed fully. The winter ideas were structural in nature; joints, texture, bark, building-block type components, like trunk, branch and cone. Angular cut-outs in angular shapes.

I find it easier to explain my sculptural work since I started writing poetry. I have no formal training in either field. I did complete the Higher National Diploma at Hereford Art College (1998-2001) but it was more the design/crafts angle that was refined during those years. This is simply personal and by no means an attempt to be clever. Although I wouldn’t call myself a poet; I was just struck by the pandemic-poetry-bug like so many others during the month of April 2020. It must be a way of letting off a bit of steam, lifting the lid and spewing out some words. I’ve noticed it takes the pressure out of the sculptural side of things, spending less time overthinking a piece is definitely better for that spontaneous, playful vibe I’m attracted to. To me a sculpture is more about what is ‘felt’ as opposed what is ‘thought’. In a poem, each word, or sentence, is assessed for its poetic value or ability to produce a certain feeling. The same is true of a ‘built’ sculpture such as “Rules of Nest Building in a Pear Tree”. Either can be assembled from components that have a relation, or an opposition to one another, and constructed in a pattern to generate verbal rhyme or visual rhythm. Creating a poem, or a sculpture, gives me an excuse to focus on what seems like detail. Detail is the fabric of life! A visual or verbal flash of inspiration brings stimulation to things that may otherwise be overlooked; it feels like finding a hidden layer, a playful transaction-less world where shapes and words are free and ample.

Dirt

On the twenty-third day I give in

and wear my workshop clothes

indefinitely

The heavy cotton burnt at the cuffs

is rigid, strong and smell

of a different time and place without

so much soap

By day I wear my leather apron

galvanised with marks

that cannot be washed away

By night I dream of heavy grit flowing

large dirt particles jamming every rift

of cracked dry human skin

In a universe of

lifting rust and frayed

fabric burn holes

I float

And wake myself up

kicking shins

with steel toe caps

Once you are familiar with blacksmithing, there is something very natural about it. You find yourself moving rhythmically between the fire and the tools, perhaps a little like a worker-ant, entranced by the work. All earth’s natural elements are present in a forge, but you don’t necessarily notice, as the fire overpowers the scene with its hypnotic qualities. You can never be sure that you know everything there is to know about metallic matter, as it’s not the sort of substance that can be calculated entirely by intelligence. Like any art form, it’s the intuitive knowledge which moves the hand holding the paintbrush, chisel or hammer.

I started casting sticks last year. Every spring for the last few years the rooks, nesting in our forge roof, have been persistently bringing their nesting material and a fair amount keeps falling through to the workshop floor. An old issue of Hephaistos magazine gave me inspiration, to fabricate some frames for the sand and I gave it a go. Generally, it was surprisingly easy. Some issues kept popping up though, as they do when you’re making it up as you go along. I’ve put most of it down to getting the moisture content of the green sand right. Also, being careful cleaning the crucible in-between use, this avoids a build-up of sticky slag, which seems to slow down the flow of the molten bronze. As you can see from the images, we forge mostly bronze. We use Coldur-A and have created rather a lot of off-cuts over the years. It turns out they’re perfect for casting!

I love welding. It’s the closest a metal sculptor comes to feeling like a surgeon. The steady hand, the white gloves, the intense observation. There is something very exhilarating about this dangerous closeness to electricity and the intense heat and glare of the melting pool. Metal sculpture is often constructed in a collage of many individual components. Like a patient in an operating theatre, the sculpture is gently stitched up and comes to life. Your own delicate heartbeat somewhere in the mix, precariously close to this circuit of current, to which you and the sculpture are interconnected by means of wires, clamps and rods.

A few years ago, we decided to try out Cor-Ten steel. I’m glad we did, because here is a material which feels like the perfect forging steel! It’s more conductive so it heats up quicker, it’s softer and it has no scale, so it takes texture really well and cleans up like that Art Deco metalwork we’ve all admired in books. For forging you just need to keep it below the melting point of copper, and it will retain its original properties. We’ve started using it on interior pieces, which is quite bonkers I guess, but if the budget is there, you know you’re going to get a superior result. We used it in the books of the “Book Tree” which was a 125-year anniversary sculpture commissioned by Saint Andrews College Dublin in 2019. The brief was ‘Ardens Sed Virens’, a line from their school crest. It means “Burning yet Flourishing” which is why we decided to burnish the backs of the 125 leaves. For this project I also created a bark-texture tool, which I have used a lot since.

I’m a little obsessed with the fish shape. After a bit of research, I was pleased to find that one of the names for the fish-shape is “Mandorla”, which means almond in Italian. It is said to be one of the most ancient symbols known to humankind. It’s also known as the “Vesica Piscis”, which apparently symbolises the sacred geometrical pattern of life on Earth. Cleary this must give me permission to indulge…! First, I did “Big Fish” in forged Cor-Ten steel. This led to “I built this fish from bark and sticks” which is a mixture of cast and forged bronze. I also used the mandorla shape in ‘Heavy Rain on the 28 March’. This was my first time to try out copper etching; I wanted to use a short poem I’d written, as a backdrop, and used Edinburgh etch with a ‘Staedtler Lumocolor permanent’ red pen as stop-out.

Michael Calnan

My first anvil experience was in 1995 with a fellow by the name of Gerald Muller, a German smith who moved to County Mayo, during the 1970’s. I met him as the tutor on a one-week blacksmithing course in Crossmolina where I made a pair of scrolling pliers and a coat rack. They were all very roughly forged compared with tools made today and were buried away from human view for a long time. Nowadays I will show the them off with pride, to illustrate my progression.

I met Gunvor, my wife and mum to our two teenagers, in college in 1998. After finishing our HND at Hereford in 2001, we moved straight into the fully equipped smithy at the National Waterways Museum, Gloucester Docks. College had been an escape from reality and deciding on what to specialize in making in the real world was quick enough really. I had finished the HND with a 300 kg freestanding cantilevered bench of 40 mm cold rolled plate and a slab of the same thickness that intersected it. A bench of Gunvor’s, forged and fabricated with blackened oak slats, along with the cantilevered one of mine, set the direction of work to be garden orientated sculpture. By 2003/4 we were exhibiting at RHS Chelsea, Stanstead Park and Hampton Court Palace flower shows.

Our current smithy is set in the demesne of Russborough House, Blessington, County Wicklow. The house is a Palladian mansion built in 1740 and located in the countryside on the periphery of the Wicklow mountains. The smithy we developed over time, has two side blast fires, a gas forge and a 2cwt clear space Massey amongst other bits. We run courses from Russborough, well Gunvor does. We used to offer lots of different projects but nowadays it’s honed down to an introductory bladesmithing course. These are very popular but due to Covid-19, are on hold for the time being.

The other aspect of our work is sculpture and our primary material is Coldur-A, a silicon bronze. Its pricey and we keep all our off-cuts and reconstitute them later in a crucible using the forge. It’s interesting to forge something that’s been previously cast as well. Patination of bronze can be challenging. I use Patrick Kippers recipes (https://www.patrickkipper.com/) and a soda blaster with ultra-fine glass for removal of oxides.

One of my theories on engaging with a creative thought process is simple. “Empty your head”, go for a long walk. Forced ideas tend to fail and disappoint. We are engaged as smiths to work with wind, water, fire and earth and sometimes find ourselves in a meditative state at the hearth. These moments, when your mind is focused/open, offer clarity in realising concepts and thoughts of form/shape. I enjoy being fully engaged with physical technique and the meditative state that sometime arrives, even if ideas don’t bear fruit. But they do come out of the blue and normally have resonance with us, which provides a strong base from which to proceed. After all, knowing what you don’t like about form and shape is as equally as important as what you do like. Confusion is often met if the clarity isn’t there. Keep it simple, don’t over complicate, be at ease, float your own boat.